| THE INDUSTRIAL RAILWAY RECORD |

© SEPTEMBER 1967 |

IRONSTONE TRAMWAYS

OF THE MIDLANDS

(5) DESBOROUGH CO - OP PITS

SYDNEY A. LELEUX

For two years I worked for a firm of accountants and made no secrets of my interest in railways. In my lunch hour I would visit quarries and sandpits near my employer's clients. My fame (!) had obviously gone ahead, because on my first visit as an auditor to the Desborough Industrial & Provident Co−operative Society Ltd. the staff were quick to show me a highly prized glass paperweight used in the office. It was the usual glass hemisphere with the design an inside cylindered Peckett 0−6−0 saddletank (in gold) engraved in the base. Encircling the locomotive were the words "Peckett & Sons Ltd., Bristol" (in red) and "Locomotive Engineers" (in blue). It was a good start to the day!

In 1913 Desborough Co−op celebrated its Jubilee. To commemorate this an illustrated history of the Society was published and copies distributed to members. I was shown one and it made fascinating reading. At one time the Society had owned much of Desborough and the surrounding country, including the village of Harrington. Here ownership was absolute, houses, shops, pub and the living of the church. The present Society President can remember the time when the Management Committee had to interview clergy when the living fell vacant.

Some of the Society's land contained beds of iron ore. In 1905 "after many dubitations and hesitations, the iron quarries were opened, and labour was employed directly by the Society to work the pits. The greatest difficulty appeared to be the placing of the stone on the market. It was thought that the great capitalistic firms would undoubtedly boycott us, as we were a Co-operative Society. These fears were found to be groundless, and the half-hearted ceased their questionings. We have constantly placed goods on the market true to the nature and quality required, and we are now recognised as reliable sellers of good-quality iron ore. Our thanks are due to our efficient representative, Mr John N. Lester (of Wolverhampton), and the practical oversight of Mr John Clarke, foreman of the works. Our output amounts of 2,000 tons per week. We employ 120 workmen, and two locomotives ply over two miles of railway. A sum of £7,000 is paid away every year in wages ....". (This amounts to an average weekly wage per man of £1/2/5d.)

For 1912 the history records that "The National Health Insurance Department was opened during the year, and at the time of the coal strike a relief fund was opened, as the quarrymen became great sufferers owing to the dispute. Relief money was advanced to them, and this has been most honourably repaid by the men, By this action we trust that the Society has made many more loyal adherents and faithful friends.

"The blight consequent on the coal strike had a serious effect upon industry. It was not anticipated that workers in other trades would have felt it so soon and for so long. It brought distress to our quarrymen. To those men who could not be kept at work it meant, roughly, a £1,000 loss in wages. The "rock-getters" could not be retained all the time. The Committee did all they could to provide employment wherever and whenever it was possible, but scores of our fellows were compelled, by forces over which they had no control, to seek odd jobs around the town. Others were forced to receive assistance in the form of loans, and others were aided by means of organised charity. The Society came forward with a gift of £21 in cash to the Relief Committee, and also gave quantities of certain soups, etc., for the feeding of those in need ....".

All material in the quarries was dug by hand. Each week the Society Manager would visit the workings to measure the amount each man had removed. Those digging ore had to be able to throw the stone up into standard gauge wagons from ground level, while the men removing overburden needed a good sense of balance to enable them to wheel a barrow of earth along the narrow planks which spanned the workings. These planks were supported where necessary by wooden trestles.

(Between the time this article was written and the date the map was drawn, the 2ft gauge system between the quarry and works was abandoned. It is for this reason that the map differs from the description of the line. Hon. Eds.)

Hunslet 1975 of 1939 with a train on the 2ft gauge line, October 1961. (Author)

The standard gauge

Planet, 3477 of 1950, at the main line junction

in October 1961. (Author)

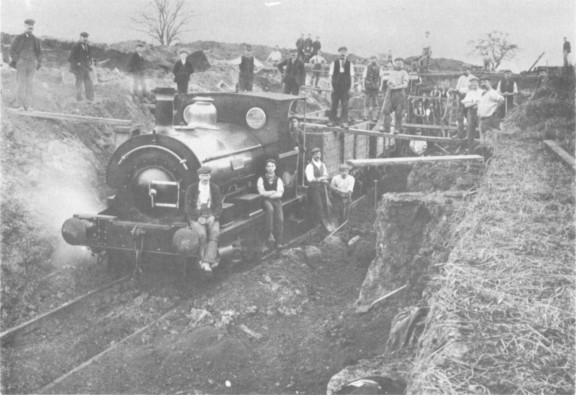

PROGRESS, Peckett

1043 of 1905, at the diggings in 1905.

(Photograph by courtesy of Desborough Cooperative Society Ltd.

The Co−op ceased quarrying about 1920* and, after a short period of operation by Cochrane & Co. Ltd., British Gas Purifying Materials Co. Ltd. took over about 1931. The ore does not go for smelting but is dried and treated in the works to make it suitable as a gas purifier. The works was formerly the Desborough Co−op Brickworks, opened in 1909. Its clay pit, now flooded and surrounded by trees, lies just behind the tip. Clay was taken to the works by a narrow gauge railway (about 2ft), presumably horse operated. No traces remain of the outside framed wooden side tipping wagons.

B.G.P.M. has two independent railways. There is a 2ft gauge line (nominally owned by a subsidiary company, the Desborough Clay & Pigment Co. Ltd) from quarry to works and a standard gauge siding to the Midland line, about half a mile away as the crow flies. The quarry line climbs out of the long cutting forming the pits and runs across a field, first at ground level and then on a low embankment, to reach the works. At the end of the embankment the line divides. The left hand track curves away sharply and terminates on an iron gantry about 12ft high where the ore is tipped. The stockpile is protected by a ridged corrugated iron roof which only just gives enough clearance for the narrow gauge wagons. Boards are laid along the gantry to enable men to reach and tip the wagons. The right hand track commences a long gentle descent and formerly ran to another quarry. Half way along the remaining section is the locomotive shed, of corrugated iron on a wooden frame. The shed has two roads, one of which is the main line to the old quarry. A wire netting fence crosses the track by the junction. This is removed when trains are running.

There are two 4−wheel diesel locomotives (Hunslet 1975 of 1939 and 2459 of 1942) painted green and orange respectively; the cabs are removable. At the time of my visit in December 1965 the green one was under repair. Six jubilee wagons are used and three or four more lie around this end of the works. A couple of old wooden wagons, a relic of horse operation, are dumped by a rotary kiln. The railway was in daily use and the ore was hand dug until the spring of 1964 when a navvy digger, operated by the locomotive driver, was purchased. Now the locomotive only works about once a week usually on Saturday mornings bringing up to the works sufficient stone for the following week. The wagons in use are stored under the stockpile roof during the week.

The standard gauge layout at the works consists of two sidings (one serving a covered loading bay) which curve through a right angle, join and then cross a high embankment at the far end of which is a brick weigh-house and single road engine shed. Originally this only held one engine, but later, presumably when JUBILEE was bought in 1913, it was extended southwards to hold two. The line then enters a cutting in which it remains for the rest of the way to the Midland main line.

Soon after the shed there is a brick overbridge and a sharp left hand curve (checkrailed). This is followed by a long right hand curve, heavily super-elevated. Another brick bridge spans the track and a long, but not so sharp, left hand curve brings the line to a dead end in a cutting beside the main line. A short trailing spur leads through a gate into a fan of sidings. One of these climbs steeply into the Co−op coal yard and the B.G.P.M. locomotive shunts this as required. The reversing neck will hold a locomotive and three wagons, although two is the maximum load nowadays.

The outstanding feature of this short railway is the track. The rail is of light section and flat bottomed, with earth, mud or leaf mould ballast; a stream flows over the sleepers between the engine shed and the first bridge. In several places old sleepers have been wedged between the rail and cutting side to stop the track moving. The cutting sides are covered with bushes and trees which overhang the track so that branches brush continuously against the train. The curves are so sharp that even when wagons are being pushed and the inside buffers are in contact the coupling is taut. Even a short railway like this is not immune from vandals, who recently dislodged the capping stones on a bridge parapet and pushed them off on to the track.

There is one locomotive, a green "Planet" 4−wheel diesel, (Hibberd 3477 of 1950). Four ex−BR wooden open wagons are used for storing bags of treated ore; about fifty tons are despatched weekly. The maximum load taken is two wagons, and trains are pushed from BR to the works. Despite the poor track a ride on the little diesel was quite smooth and free from the jolts I expected although low speeds no doubt contributed to this. The locomotive is fitted with rail washing gear, the water being contained in an oil drum mounted in the cab. Beside the drum stands a coal scuttle full of sand.

Although the Desborough Co−operative Society itself no longer quarries stone it owns the land and receives a rent and royalty, thus maintaining a connection with the ironstone industry which has existed for over half a century.

I am indebted to the Manager, Mr V. Panter, for permission to quote from the Jubilee Book and reproduce illustrations. I must also thank Mr J. Reynolds who introduced me to this material in the first instance.

* The history of the quarries is covered in detail on pp. 118-120 of "The Ironstone Railways and Tramways of the Midlands" by Eric S. Tonks.